In honor of International Women’s Day, we wanted to give our photographers the opportunity to get to know one of the most industrious and passionate photographers and storytellers of this decade.

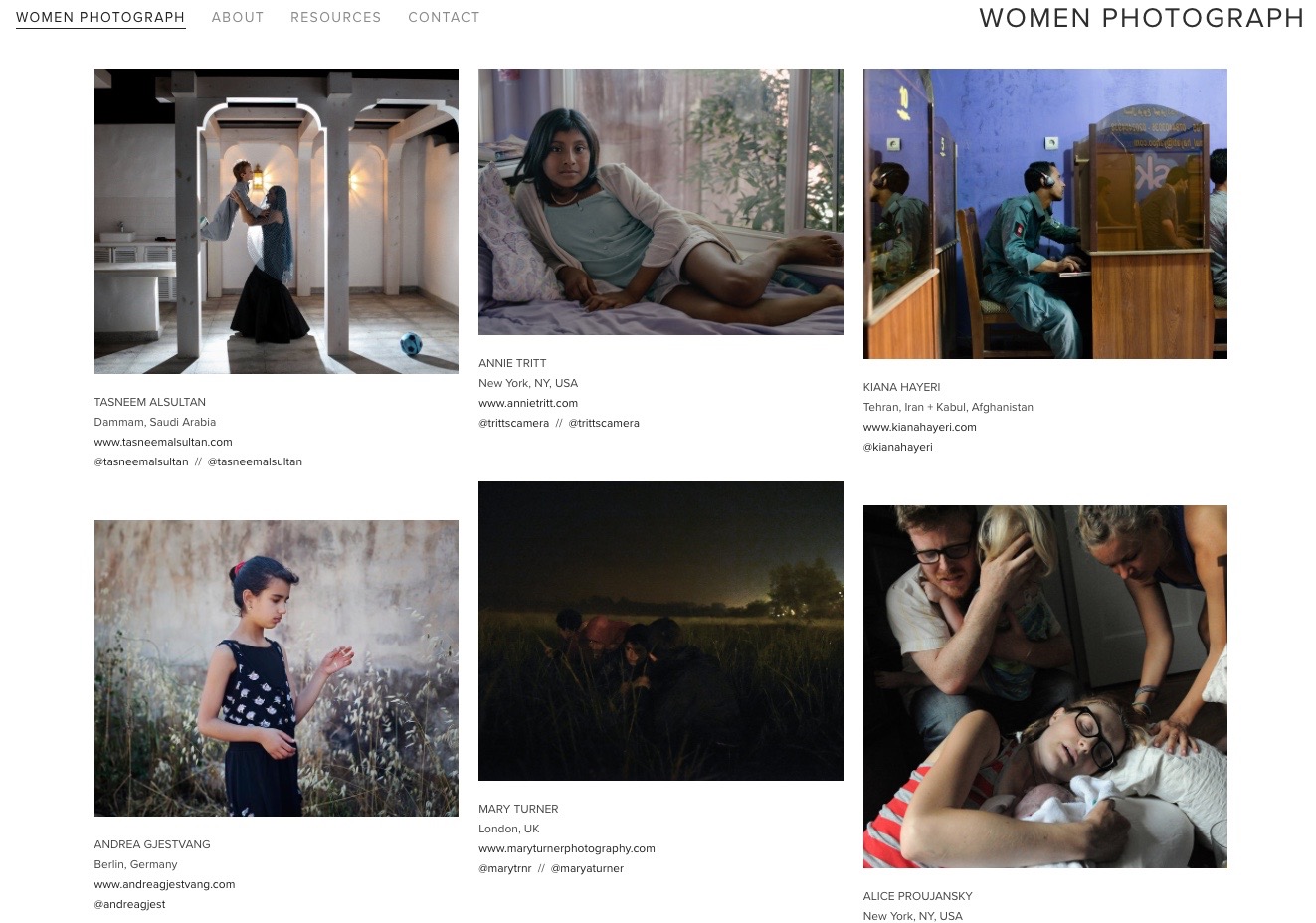

Daniella Zalcman is a photojournalist and multiple Pulitzer Center grantee who could have been satisfied with great news assignments from some of today’s top newspapers and magazines—but she has chosen instead to unite her talent with purpose and passion, focusing her photographic efforts on exploring the effects of colonization on native peoples and expanding opportunities for female photographers with her website (announced last month), Women Photograph.

Daniella is garnering industry accolades for her deeply resonant and truthful images of Indigenous people. Her recent book, Signs of Your Identity, showcases powerful portraits of Indigenous Canadians who were forcibly sent to Indian Residential Schools and chronicles their haunting stories. In 2016, Signs of Your Identity won the FotoEvidence Award, which recognizes one photographer whose work demonstrates courage and commitment in the pursuit of social justice.

We asked Daniella to talk about her work, her thoughts on women in photography, and any ideas she has about how to tell a photographic story that reaches out from the page or screen. Enjoy!

–

500px: March 8 is International Women’s Day. You have created a website, Women Photograph, devoted to women. Why was it important to you to create this database focused on female photographers?

Daniella Zalcman: There’s a major diversity problem in the photojournalism world right now. (Probably across most subgenres of photography, but I’m intimately familiar with the documentary photography world so I’ll speak to that.) That’s a huge problem. Photojournalists are responsible for how we see the rest of the world—it’s how we access imagery of people we may never meet and places we may never visit. If we want to document those people and places with nuance and sensitivity, we need to be doing it as a diverse community of storytellers.

500px has a wide variety of member photographers—some hobbyists and all the way to professionals. For those looking for mentorship, what advice do you give them regarding…

Increasing technical skills:

Ah, I’m not qualified to give technical advice. I never studied photography and in many respects I still don’t really know what I’m doing. Just go out and shoot!

Growing a network:

For me, this is one of the least fun parts of my job, but it’s incredibly important. At least in the photojournalism community, publishing is heavily contingent on editors liking your work AND liking you as a person—no one wants to spend days or weeks working on an edit of a big project with someone who’s unpleasant. So, don’t be unpleasant. Beyond that, practically, I find Twitter and Instagram are incredible tools for getting my work seen by people I wouldn’t normally interact with, and if you have the time and wherewithal to do it, some of the bigger photo festivals and events like Photoville, Rencontres d’Arles, Visa Pour l’Image, and so on are great places to connect with editors in person.

You were recently named one of the PDN 30. Congrats!

You say you are not particular to any camera or stylistic approach, preferring to focus on “being consistent in incorporating and invoking the voices of the people you photograph.”

Can you explain that a little more?

There are some photographers who have very distinct visual styles—in how they shoot, in how they edit—you can look at an image and immediately know, “Oh, that’s Eugene Richards.” There’s something very practical and powerful in that consistency. But with me, for better or for worse, I like to keep experimenting and trying different things. I shoot with four to six different cameras on a regular basis. I use a lot of alternative processes in my documentary work. The thing that I’m dogmatically true to is the ethical presentation of the stories I’m telling, to think about the journalistic process and how we can make it more transparent, more honest, less colonial. That’s what I think about most.

Where did your interest in the impact of imperialism begin?

I never really learned about colonization in high school or college (the latter being more to do with the fact that I studied architecture than with a failing of my university, but still). We didn’t talk about what happened in the Belgian Congo or what the British did in India or how the French impacted Haiti. And as I started traveling as a young journalist, I was struck by how often that influence went undiscussed and unexplored in a modern context. I was working in Uganda looking at the evolution of the anti-homosexuality law that was, briefly, on the books there—and I was struck by how much the rise of homophobia and criminalization was influenced by British colonial rule and, later, the American evangelical presence. It’s easy for us to look at countries that currently have anti-gay laws and think that it’s so backwards, so unmodern—but we have to take the time to investigate the roots of those sentiments. Almost all of my long term projects now in some way look at the modern legacies of colonialism.

Tell us about Signs of Your Identity. 500px is a Canadian startup, so your Canadian chapter is of particular interest.

Signs of Your Identity explores the legacy of forced assimilation policies in Indigenous communities. It began in Canada in 2014 while I was actually researching an HIV story, and realized that almost every person I interviewed was referencing something called residential school. I’d never learned about Indian Boarding Schools in my history classes, and was horrified when I started reading more about the Canadian government’s policies. In short, Indigenous children were kidnapped from their families and communities and sent off to boarding schools where they were explicitly whitewashed—punished if they spoke their own languages or practiced any form of their culture or spirituality. There was widespread physical and sexual abuse, and in some extreme cases even medical experimentation and forced sterilization. Those schools ran until 1996 in Canada.

You have just been to Standing Rock. Will the American chapter focus upon this or another matter?

The American segment of the work is entirely focused on the legacy of Indian Boarding Schools—by complete coincidence, I happened to be working in Lakota communities last summer and one of the people I interviewed told me that he was going to a pipeline protest and I should come along. I did, and was lucky enough to witness the early days of the Standing Rock protest movement. It’s all part of the same body of work, in the end—looking at our governments interact with Indigenous populations, at how modern policies continue to function as tools of erasure and cultural genocide—but Signs of Your Identity specifically will focus on the boarding school experience.

You seem to be an amazing creator, with a multi-faceted approach to creation. How do you find the time to conceive projects, shoot, collaborate with others, write books, create and run Women Photograph, and even create classroom curriculum for Signs of Your Identity?

I don’t sleep much.

You were an architecture major in college. How did your interest in photography arise?

I’ve wanted to be a journalist since I was 12 or so—first as a writer, and then as a photographer once I got to college and started shooting for my university’s student newspaper. For pretty much as long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to tell people’s stories.

Do you recall the first photograph you thought was good, or the moment yours would be a life led by a passion for pictures?

I started working for my student newspaper as a writer—I’d always enjoyed photography as a hobby, but never really considered it much in the context of my interest in journalism. One day early on in my time at the newspaper there was some crisis and the then-photo editor asked me to take a last-minute assignment photographing the Attorney General John Ashcroft. It was an unremarkable assignment—man at podium, etc.—but even then, I was hooked. Not too long after that, I ended up getting my first assignment for the New York Daily News photographing Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, which ran on the front page of the paper the next day, and I never looked back.

–

Check out Daniella Zalcman’s website and follow her on 500px.

Leave a reply