A pink chair overlooking a vast blue glacier. A view of an ice floe under a blazing golden sky. A bathtub in the middle of a picturesque wetland. These places might not exist in the “real world,” but last year, they were brought to life by the influential artist Alexis Christodoulou. A collection of nine 3D rendered landscapes, featuring gravity-defying architectural elements and design details, were then sold as NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, for the equivalent of roughly $340,000 in total.

Christodoulou’s meditative, ethereal project isn’t the only work of digital architecture to hit the blockchain recently. Early last year, Krista Kim’s Mars House, a digital house created on an iPad, sold for the equivalent of around $512,000, making headlines worldwide. It was the artist’s “dream home.” Last summer, Christie’s auctioned ten pieces of digital furniture created by the artist Misha Kahn: a coat rack, a sconce, a table, and more, each more colorful and futuristic than the last. The pieces were sold as NFTs representing the 3D models, though collectors could 3D print or commission a physical version.

Separately, the digital artist Andrés Reisinger made a splash with The Shipping Collection, an NFT project comprising ten digital works. That collection sold for $450,000, with owners able to upload, show off, and use their pieces in virtual video game worlds like Minecraft. Some of the pieces were later created IRL (in real life) as physical objects.

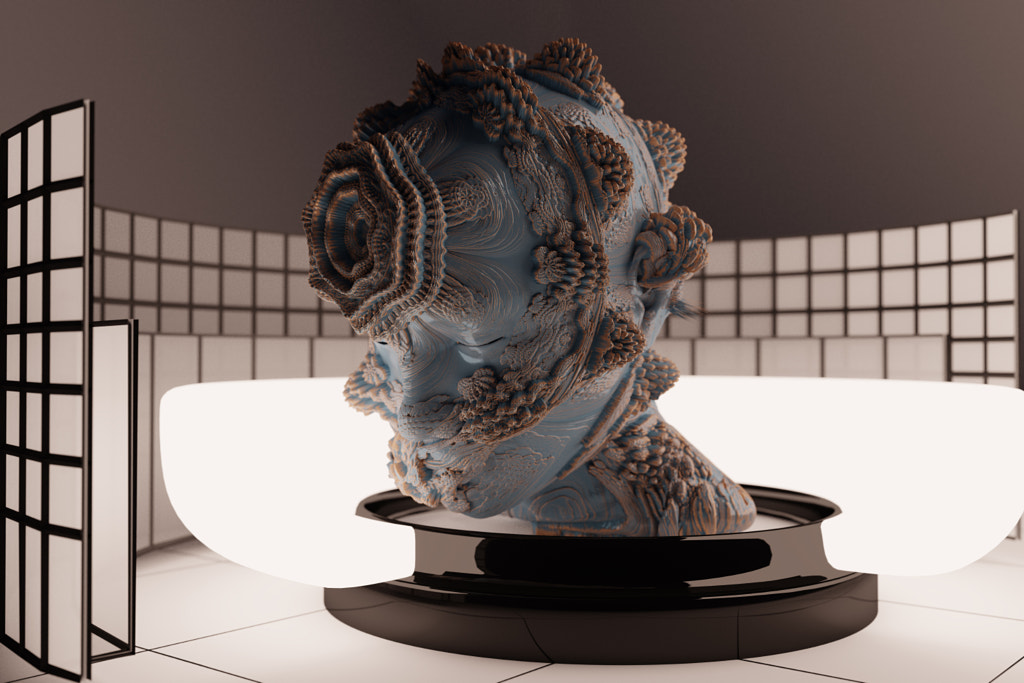

Today’s 3D rendering tools offer photorealistic lighting and textures, and the technology continues to improve, as artists push the boundaries and blur the line between the “real” and the virtual. In years gone by, architectural renders were used mainly to visualize buildings that would someday exist in the real world, serving a mostly practical purpose. But now, blockchain technology has allowed us to buy and sell objects that exist purely in the digital realm—including imaginary, fantastical structures that would be impossible in the real world.

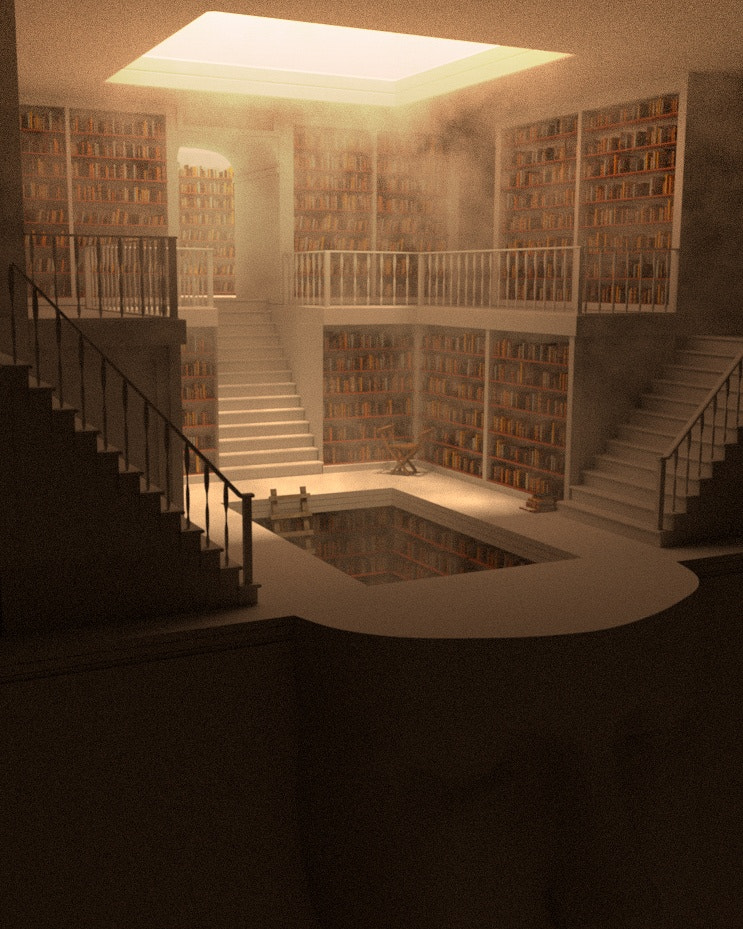

In this new era, these kinds of artworks and architectural plans, once purely functional, have value in and of themselves. One interesting application of this idea can be found in Architoys, a project by Zyva Studio’s Anthony Authié and the visualization artist Charlotte Taylor. Sold as NFTs, the project includes a range of capsules that contain and display fantasy architectural spaces sprung from the artists’ imaginations.

Aside from more traditional forms of art, collectors in the age of Web3 can acquire and claim verifiable ownership over digital buildings, houses, or even furniture. They can interact with these spaces through a VR headset, or they could invite others to view their collections as part of a metaverse gallery exhibition. While the idea of owning a house you can’t physically inhabit might seem foreign now, it’s quickly catching on.

The promise of metaverse—a hypothetical virtual world where we can hang out, go to work, see art, and buy things—has proven appealing to established architects, including Patrik Schumacher of Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), who is designing a city. Inside this virtual city, you can find a central plaza, galleries, and more, inspired by the history of ZHA and its buildings. Plus, hovering rooftops and expanding auditoriums.

Meanwhile, digital architecture firms have staked their claim to the metaverse as well. Voxel Architects, a company that designs virtual buildings and works with 3D modelers to create them, helped bring the Sotheby’s Decentraland gallery to life last year. Clients are paying big money for their expertise, as a single project can cost $300,000.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that the demand for 3D renders is there. Last year, The New Yorker covered the phenomenon known as “renderporn,” citing the rise of meditative CGI interiors on social media. During the pandemic, these spaces provided an escape and encouraged us to dream of faraway places, even when we were stuck at home. And when NFTs emerged into the mainstream, it became clear that people will pay for some of them as they might a real-life vacation home.

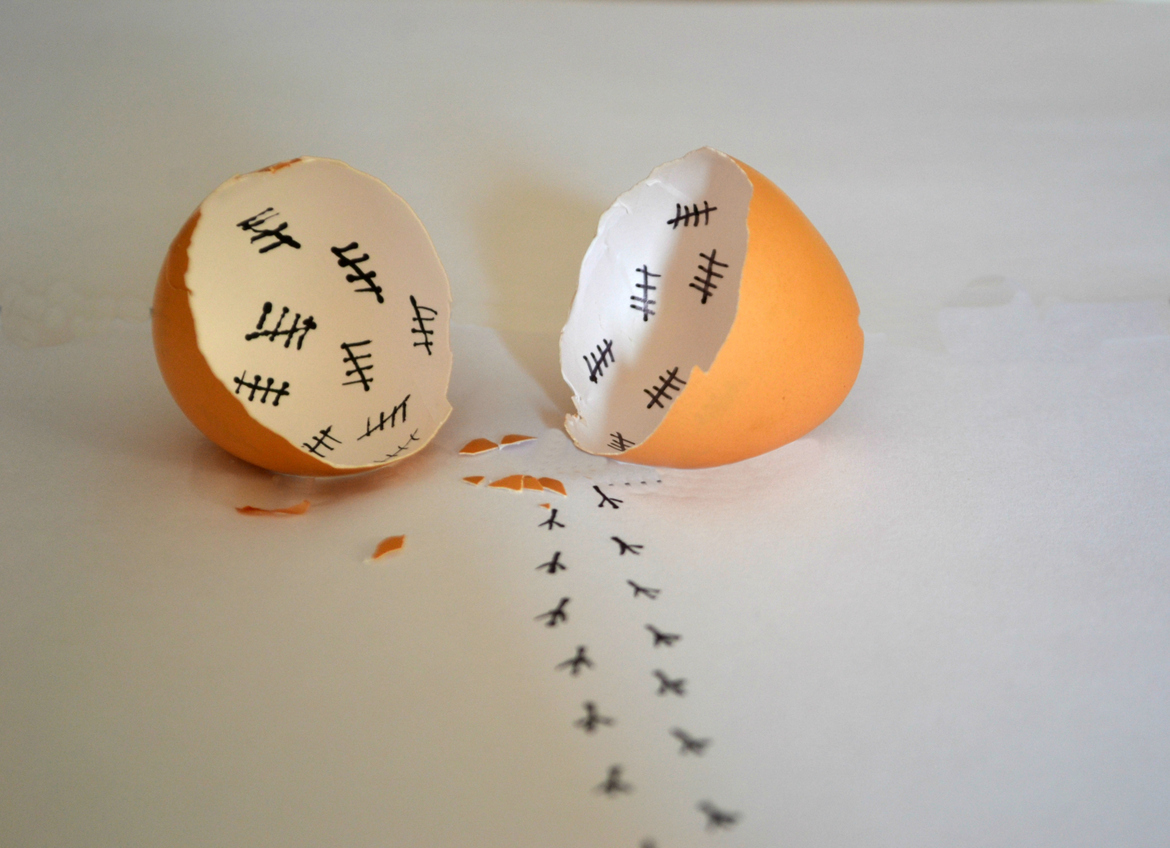

It’s still early days, but some hope that this larger cultural shift in how we think about design and architecture could help create a more level playing field. In the traditional art and real estate industries, you need financial backing and substantial resources to design a building or get your photographs exhibited in a gallery. But in the metaverse, the goal could be for everyone to be able to build, using software and tools that are increasingly accessible and affordable.

Ideally, you won’t even need to be based in a big city to land a major commission or gallery show—as long as you have internet. The hope is that there will be fewer hoops to jump through—and no centralized powers to act as gatekeepers. In a decentralized world, the community decides what gets built and what doesn’t, not a single person with the power to approve or veto a project.

Even for artists outside of the 3D space, interest in digital architecture could have long-lasting implications, including how and where photography is exhibited, seen, and enjoyed. Instead of hanging a traditional print on a blank wall, you could have pictures that move, such as cinemagraphs. Or you could have a picture frame that moves around a virtual space, interacting with guests in real-time. Photographers could even build their own spaces, tailored to their work; we’re still restricted, in some ways, by the existing technology, but in the future, the possibilities feel limitless.

Of course, photographers can also draw inspiration from architects, and vice versa. Last year, An Rong and Elisabeth Johs curated a virtual gallery exhibition called Invisible Cities, featuring artworks inspired by the book of the same name by Italo Calvino. Photographs, 3D art, traditional painting, digital paintings, virtual reality, pixel art, voxel dioramas, and more were included.

Going forward, we might see the lines between media continue to blur and expand. “From punchy color palettes to saturated, AI-rendered skies, the aesthetics of the wider space is likely to influence photography as well,” the 500px team tells us. On VAULT by 500px, one artist who’s transitioned from photography into 3D art, with both practices informing her work, is Elnaz Mansouri, whose otherworldly creations are inspired, in part, by magical realism. Using Cinema 4D, she transports us to landscapes, rooms, and spaces inspired by memories and emotions—but unrestricted by the rules of space, time, and gravity.

Explore VAULT now. An NFT marketplace for creators, collectors, and art lovers.

Leave a reply