As a top Licensing Contributor, the Saint Petersburg-based photographer Renat Renee-Ell never forgets her model releases. “You don’t want to spend the time and effort executing an idea, only to realize you don’t have all the rights to your work,” the artist tells us. Before collaborating with someone new, she sends an email outlining the purpose of a release and a PDF version to print out and sign prior to the shoot.

Knowing when you need a signed model or property release (and when you don’t) is crucial if you want to license your photos commercially. These legal documents protect you, the model or property owner, and the buyer from any confusion down the line. While most situations are pretty cut and dried, there are a few gray areas when it comes to model releases. Here’s a breakdown of some common misconceptions and the facts behind them.

Myth: No face, no problem.

Fact: You can recognize people without seeing their faces. Even a turned back can reveal a person’s identity, given the right context.

“I once had a very promising image rejected from commercial Licensing due to the fact that I could not provide a model release for an individual in-frame who was facing the other direction,” top Licensing Contributor Aidan Campbell explains. “This was in a popular tourist destination, and the reason for rejection was that the individual would be able to recognize themselves in the image based on their clothing. When in doubt, have a model release signed!”

Myth: You don’t need a release if it’s your own family.

Fact: You absolutely do. If you’re photographing your children, you’ll need to sign the model release as both the parent/guardian and as the photographer. If you’re working with relatives, you’ll need to get their information. If you’re uploading a self-portrait, make sure you’ve signed as the model as well as the photographer.

Myth: Photos of hands and feet do not need model releases.

Fact: It depends. Can you identify the person from an unusual birthmark or scar? In that case, you’ll need a model release. The same might apply for cases with distinct jewelry or tattoos. Bridal Hands by Muhammad Ali Mir is an excellent example of a hand photo that needed a model release.

Hardi Saputra is a top Licensing Contributor and a conceptual still-life artist. He rarely photographs people, but he does occasionally incorporate his hands in an image. In most situations, it isn’t necessary for him to have a release because his hands aren’t recognizable, but he still makes a point of signing them just in case it comes up down the road.

Myth: Street photos don’t need property releases.

Fact: It’s all about the details. Streets are public places, so for the most part, they won’t pose issues. However, it’s essential to keep an eye out for any, and all, intellectual property. For example, is there a sculpture or graffiti in the background? If so, you’ll need permission from the artist.

What about a storefront for a restaurant or boutique? In that case, the owner will have to sign. Something as small as an Apple logo could prevent your image from being sold commercially, so frame your shots with care.

Myth: Tattoos are fair game.

Fact: This is a tricky subject. Tattoos can identify a person, so they provide clear grounds for a signed model release. What might surprise you, however, is that you may also need a property release.

Winnie Bruce, a top Licensing Contributor, recently photographed someone who’d had some ink done by a well-known artist. “Because that tattoo is the intellectual property of the tattoo artist, I had to decide whether to frame where it’s hidden, or to frame where it shows and ask for a release,” she explains. “I chose to crop out the tattoo when I was framing.”

Myth: Releases are only for humans, not animals.

Fact: There are exceptions, including well-known pets. If you’re photographing an Insta-famous cat, a dog who stars in a TV show, or a best-in-show winner, you might need a property release.

Myth: Skyline photos don’t need a release.

Fact: It varies. While a wide shot of a city skyline in silhouette might be unlikely to cause problems, some buildings are protected. For example, if your New York City skyline shot features a close-up on the Empire State Building or the Flatiron Building, you might not be able to license it commercially.

Usually, it comes down to the question of whether or not a protected building is the primary focus of your photo. If it’s just a tiny detail, it’s probably fine, but if it’s your star subject, you could run into trouble.

Myth: Public landmarks aren’t protected.

Fact: Some are. Even though the Hollywood Sign, Disneyland, and the Frank Lloyd Wright buildings make for great photos, they can’t be licensed for commercial use, with a few rare exceptions (e.g. the Hollywood Sign is part of a larger skyline, not the main focus).

You can use images of the Eiffel Tower for commercial purposes, but only if it’s during the daytime! Nighttime shots of the tower won’t be accepted.

Myth: If you remove the logos, you’re good to go.

Fact: Not always. Some brands restrict not only their logos but also their colors. Tiffany & Co. and Christian Louboutin are some of the better-known examples. Even if you edit out all the text and branding, you cannot license photos of those red-bottomed shoes or blue boxes for commercial use. The same applies to the colors and design of a Rubik’s Cube, regardless of whether or not you can see the logo.

Myth: All privately owned places require a property release.

Fact: Not necessarily. If you can recognize or identify the location, you will need a release. If you can see street signs, numbers, unique architectural details, or distinct pieces of decor, contact the owner for permission.

But if the location cannot be identified from your photo, you might be in the clear. For instance, if you use your kitchen table to stage a food shoot, you might not need to bother with a release. This photo by Michael Osterrieder also does not need a release because we can’t identify the arena based on this close crop of the chairs.

Myth: It’s pointless to photograph a crowd.

Fact: There are ways to do it right. If you’re at a concert or in the middle of a protest, you won’t be able to get releases signed by every single person in the frame. Still, that doesn’t mean you can’t license them commercially.

Use silhouetting to obscure the identities of individuals in the distance, or choose a long shutter speed to create blur. You’ll have to be careful and ensure that no one is recognizable, but it can be done.

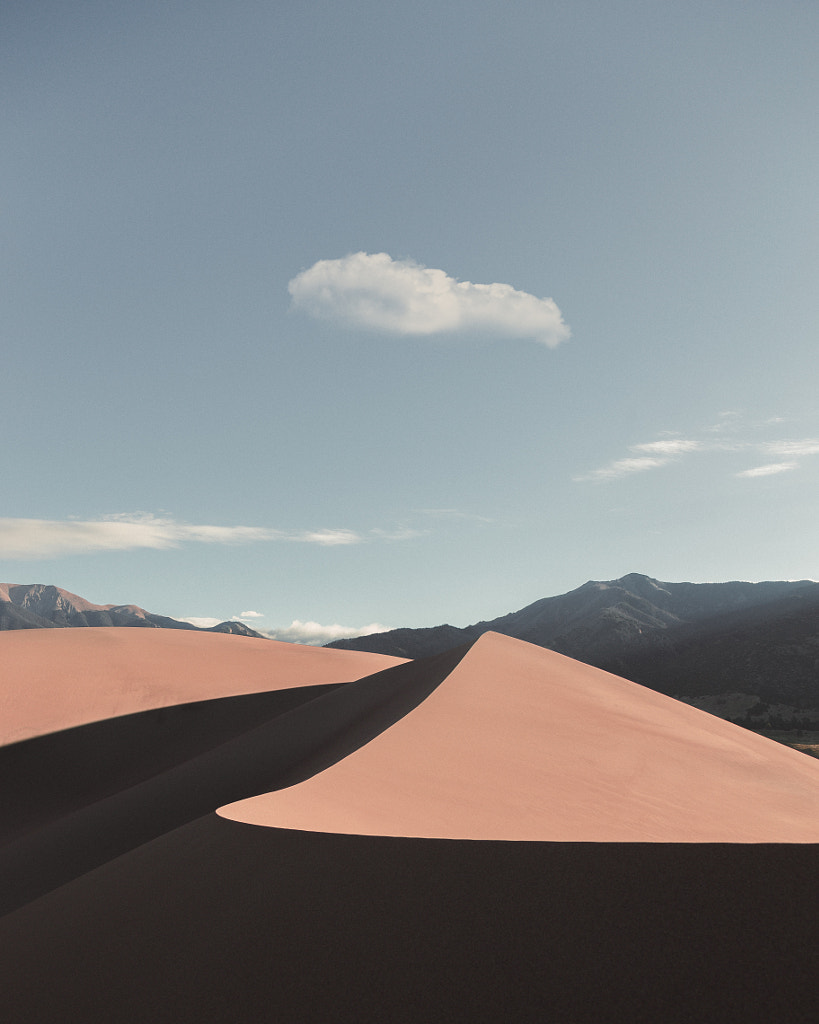

Myth: You should always submit a model release, just in case.

Fact: In cases where you clearly do not need a release, submitting one anyway is counterproductive. According to Dave Fitzsimmons, Asset and QA Supervisor at 500px, it’s not uncommon for photographers to upload a model release for images where it doesn’t make sense, such as a landscape. If that happens, the release will need to be removed and the image submitted again. In straightforward situations, save yourself the extra hassle and don’t bother with a release.

Myth: All releases are created equal.

Fact: Depending on the agency, you might need a certain type of release. Feel free to download the recommended 500px model release and print some copies for future use. You can use another format if you prefer, but you’ll need to include all the same details.

Learn more about 500px Licensing.

Leave a reply