When Vadim Balakin encountered the remains of a polar bear in Northern Svalbard in August of 2014, the cause of the animal’s death was unknown (pictured below). It might have been old age; however, the good condition of the teeth suggested that starvation was also a likely possibility. “They say nowadays such remains [are] to be found very often,” the photographer explained at the time.

At that point, we knew that climate change and the melting of sea ice would continue to affect the polar bear population, but the photograph brought that fact home and made it personal. In 2016, it won the environmental issues section at National Geographic Nature Photographer of the Year and went on to be seen by people across the world. For many, it became an emblem and a call to action to protect this vulnerable ecosystem. Last year, that call was amplified by further research indicating that melting sea ice posed a serious threat to the survival of Svalbard’s polar bears.

Photographs like Vadim’s have the power to inspire action, on a personal and institutional level. In the last decade, social media has expanded how we view and share pictures, allowing documentary photographers and photojournalists to make a difference on a global scale, whether they’re documenting environmental issues or social movements. In this brief guide, we’ll explore some ideas for creating images that spark change, while also tracing the history of documentary photography and its enduring influence over our world and culture.

Consider your community

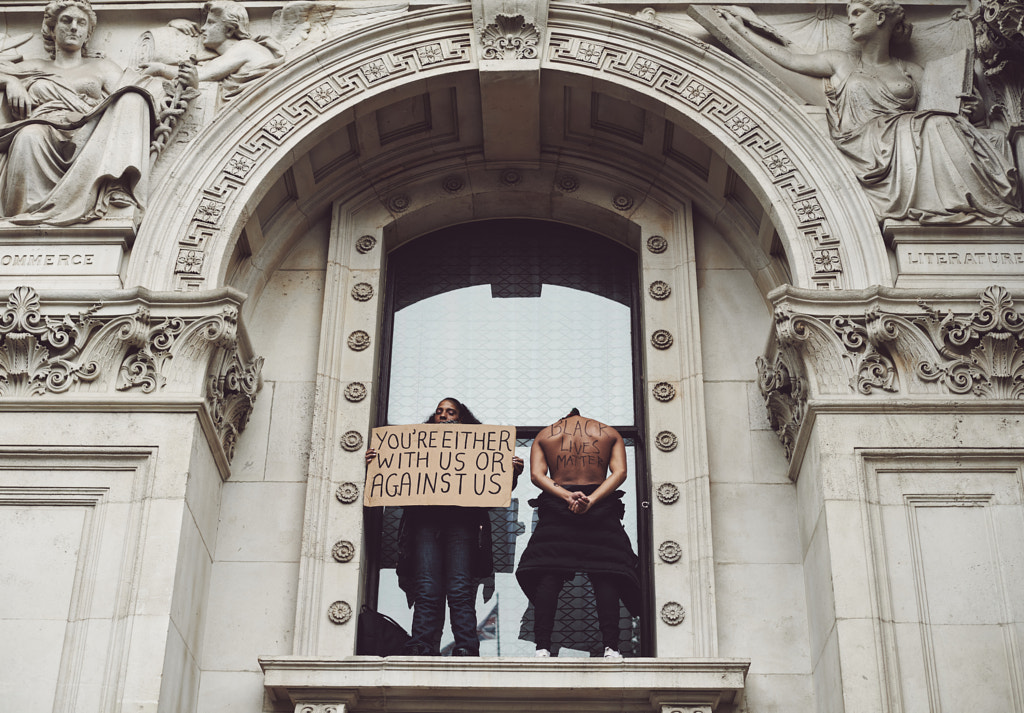

Documentary photography is a long-term commitment, so it can help to choose a story close to home or within your own community. As you’re not an outsider looking in, you’re best equipped to understand the nuances at play, and your knowledge goes a long way toward establishing trust. Avel Shah, for example, has been documenting activism throughout his home base in London for years, from the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 to the anti-war protests for Ukraine in 2022.

During the pandemic, in particular, as many photographers found themselves unable to travel, they discovered important stories in their own cities. Laura Moraña, for instance, documented the experiences of Christina, a hospital worker at Hospital Evita de Lanús, close to where she lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Put in the time

Of course, that’s not to say you’re limited to local stories alone. You can travel halfway around the globe, but wherever you are, make sure to connect with the local community and learn as much as you can about the place and its history. See if local photographers have already covered the story, and if so, connect with them to see how you can help. Spend time with the community and its leaders before ever bringing out your camera. Putting in that time will also allow you to see beyond the headlines to discover sides of the story others might have missed.

Although we live in a fast-paced world, it’s worth keeping in mind that social documentary projects can take months or years. After all, Lewis Hine, whose photographs were instrumental in bringing about child labor laws in the United States, documented the living and working conditions of children across the country from 1908 to 1924, giving him the experience to understand the scope of the problem.

Show respect

As a documentary photographer, you have a responsibility to be accurate and thorough. That includes abandoning stereotypes and learning to identify—and leave behind—your own assumptions and biases. Look beyond what you think you know, and listen to the people you’re photographing.

Also, if you’re exploring activism through photography, consider where your photographs will be published and what kind of consequences they could have for the people pictured. Photography can help, but it can also cause harm to vulnerable communities, so be thoughtful about how you approach sensitive subjects. Where possible and appropriate, seek consent.

Look at every angle

When the photojournalist Skanda Gautam covered the wildfires in Nepal last year, he documented the blanket of haze that surrounded Kathmandu valley, an environmental activist in protest, a helicopter fighting the fire, and the fires themselves. As the country combatted the worst forest fires in years and air quality dropped to hazardous levels, he showed us what was happening in real-time, from every angle.

Even if you’re documenting a story that’s been widely covered, consider digging deeper. Beyond the headlines, who are the people most affected? Who’s helping, and who’s advocating for change? Finally, what moments give you hope? While photographing daily life amid the pandemic in Kuala Lumpur, for example, Mishan Jay encountered this florist, providing a touch of color to an otherwise uncertain time. Moments like these, big and small, can be discovered once you look for them.

Be unobtrusive

Showing respect also means respecting people’s space at vulnerable moments. In some cases, that might mean not photographing them at all. In others, the urgency of the situation and the need to share the truth might outweigh all other considerations. That’s a judgment call personal to each photographer. But either way, avoid intruding on someone’s space. When working as a war photographer, Robert Capa used an inconspicuous 35-millimeter camera that allowed him to get close without interfering or influencing the events around him.

(The exception, of course, would be in cases where you can help. In emergency situations, put your camera down and provide any assistance you’re able and qualified to provide.)

Provide context

Dorothea Lange famously covered the Great Depression for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), raising public awareness and ultimately resulting in aid for desperate families. According to historians, however, she was angry throughout her life that her photographs were regularly published without captions. At one point, Migrant Mother, perhaps the most iconic photograph of the Depression era, even appeared in advertisements, which Lange vehemently opposed.

Decades later, we understand the dangers of documentary work being taken out of context. Consider, for example, the fires that devastated the Amazon in 2019. As the Amazon burned, the public shared photographs to raise awareness, but a few of the images that went viral did not show the actual fires, as some had been taken years earlier or in different locations.

In the age of social media, providing accurate and thorough context is essential, especially if you’re using photography for change. Make sure to include detailed captions; it can help to take notes in the field or use a recorder so you remember all the details.

Keep in touch

True change doesn’t happen overnight, so maintain those connections you forged while documenting your story. Reach out early to activist groups, non-profit organizations, and individuals making a difference, and stay in touch with them. These relationships could also help you forge connections in the future through word of mouth.

Another idea is to give back directly through donating or volunteering with one of these organizations; your research on the ground will help guide you in the right direction and inform you on where your resources are most needed and could do the most good.

Not on 500px yet? Sign up here to explore more impactful photography.

Leave a reply